It is looking more likely that the Seattle area’s $54 billion ST3 light-rail extension will be approved. I voted against it. Here is why.

Being cool isn’t the same thing as being effective

Underlying many of the pro-light-rail arguments that abound — at least those by the casual voter I see on Facebook and overhear around the city — is an air of coolness and futurism. This isn’t articulated explicitly, but here’s a thought experiment to get my point across: suppose we had a ballot proposal to spend $54 billion on a bus expansion package (bus only express lanes, new long-range hybrid buses, more city-to-city bus routes, etc.). What would the reaction be? Probably something like, “Are you kidding me, $54 billion for a bunch of buses?!?! We could build light-rail for that much!” We could (or maybe not as I’ll discuss), but the question is why is light-rail inherently better than other alternatives?

What I hear most are rants about how China and Japan have high-speed rail, how Europe survives on it, how great it was to visit San Francisco and be able to take the BART. Obviously all of this is awesome so of course we should have more rail lines.

Yes, it is indeed great to rail around San Francisco on a train system that you did not pay to construct and do not pay to maintain in a city in which your main purpose is sightseeing not living and commuting to work. But the year is now 2016 and the question is whether we should spend $54 billion and 25 years building a light-rail system or think harder about the alternatives.

It doesn’t pass the sniff test

The one argument you do hear regarding the ST3 expansion is Seattle’s increasingly horrendous traffic. The scrawling of Seattle locals on Facebook every time a new “Top 10 Worst Cities for Traffic” is a smug reminder that if light-rail would’ve actually gotten funded 30 years ago “when it should have” that we wouldn’t have this traffic problem: “Gee, do you think we need light-rail?” the fake rhetoric proceeds.

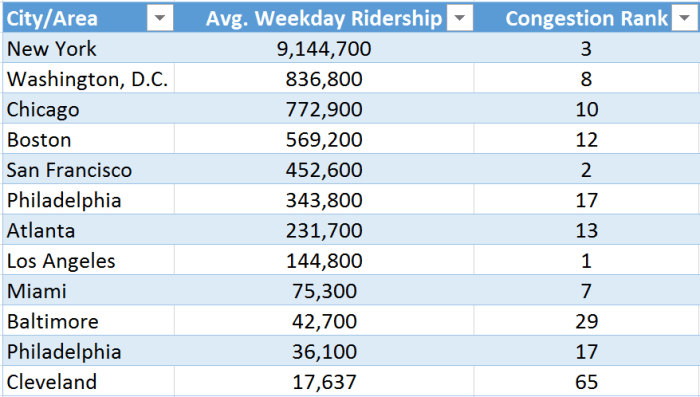

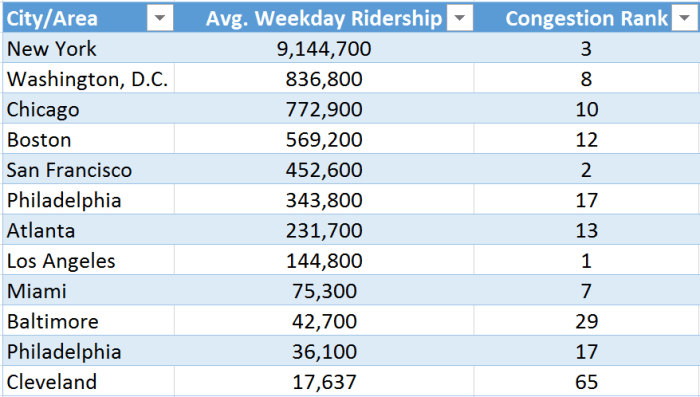

But this argument doesn’t pass the sniff test. Rail ridership does not largely correlate with reduced congestion. I put together a simple dataset to show this (table below). Many of the cities with the largest weekly U.S. rail ridership also have the worst congestion.

Does this simple table prove we shouldn’t expand light-rail? No. It’s only a sniff test. But that’s precisely the point. The story is more complicated so we should think harder when drawing a direct line from Seattle’s congestion problems to its lack of expansive rail.

(By the way, researchers have found similarly negligent effects on congestion from light-rail and here is more research on the issue).

The project violates a basic economic principle

The principle being that projects should be paid for by the people that use them. Although this principle is mostly adhered to in the current budget, there is still $4.67 billion in federal grant funding meaning tens of millions of Americans that never ride Seattle’s light-rail will end up paying for it. Sure, we end up paying for a bunch of projects we’ll never use in cities we’ll never visit, but that doesn’t mean we should impose the same cost on others.

The principle is violated at the local level too since every tax payer will help front the bill for light-rail regardless of whether they end up riding it (a very small portion of operating costs come from fare revenue).

It costs ALOT (and will probably cost more)

It costs $54 billion!!! That’s a lot of money!!! And $28 billion of that is increased taxes. And that’s a lot of money!!! Sure cost alone does not indicate the merit of a project, but it does mean we should think really, really hard before moving forward. And it puts the onus on the proposers to make a very strong case about why the project is going to be awesome. In my view they haven’t done that.

And if history is any indication it could actually cost (much) more. This was written about the original lightrail project back in June of 2013:

Sound Transit’s light-rail system, called Link, has also had its share of challenges. The 25 miles of light rail that voters were told would be completed by 2006 at a cost of $1.7 billion, have resulted in 23 miles of track which, when completed, will end up costing $5.2 billion.

In other words the project cost 3 times more than originally projected for two fewer miles.

Overruns of these magnitudes are the rule not the exception. Here, Bent Flybbjerg has done great work (I recommend this interview). His research on megaprojects is gloomy (a megaproject is one that costs more than $1 billion and affects more than 1 million people). In a 2014 paper he wrote the following (emphasis mine):

Performance data for megaprojects speak their own language. Nine out of ten such projects have cost overruns. Overruns of up to 50 percent in real terms are common, over 50 percent not uncommon. Cost overrun for the Channel tunnel, the longest underwater rail tunnel in Europe, connecting the UK and France, was 80 percent in real terms. For Denver International Airport, 200 percent. Boston’s Big Dig, 220 percent. The UK National Health Service IT system, 400-700 percent. The Sydney Opera House, 1,400 percent (see more examples in Table 2). Overrun is a problem in private as well as public sector projects, and things are not improving; overruns have stayed high and constant for the 70-year period for which comparable data exist. Geography also does not seem to matter; all countries and continents for which data are available suffer from overrun. Similarly, benefit shortfalls of up to 50 percent are also common, and above 50 percent not uncommon, again with no signs of improvements over time and geography (Flyvbjerg et al., 2002, 2005).

ST3 will serve mostly current transit riders

The Washington Policy Center used Seattle Sound Transit figures to estimate that only 28 thousand new daily riders would be added by 2040. What they found is, well, troubling (emphasis mine):

This means that under ST3, each new transit rider will cost over $1 million dollars.

It also means that 97% of the one million new residents expected in 2040 will likely not be using Sound Transit’s costly services, meaning Sound Transit officials do not meet the demand for mobility they themselves anticipate.

If Sound Transit officials want to keep hypothesizing what they can do in theory – using the median price of a single-family home in King County, they could buy every new passenger a home and still have plenty left over ($38.2 billion) for:

– 8,000 new hybrid articulated buses

– Paying back taxpayers for the SR 520 bridge replacement

– Eliminating tolls and providing tax relief on the Viaduct replacement project

– Expanding I-90 through Snoqualmie Pass

Yet even after all this spending, they would still have enough left to buy those same homes for the 4,505 homeless people in Seattle, ending homelessness in the city with $21.8 billion still left in their bank accounts.

And here’s the abstract of a 2015 study making a similar point (emphasis mine):

We examine American support for transit spending, and particularly support for financing transit with local transportation sales taxes. We first show that support for transportation sales tax elections may be a poor proxy for transit support; many voters who support such taxes do not support increased transit spending, and many people who support transit spending do not support increased sales taxes to finance it. We then show that support for transit spending is correlated more with belief in its collective rather than private benefits—transit supporters are more likely to report broad concerns about traffic congestion and air pollution than to report wanting to use transit themselves. These findings suggest a collective action problem, since without riders transit cannot deliver collective benefits. But most transit spending supporters do not use transit, and demographics suggest they are unlikely to begin doing so; transit voters are wealthier and have more options than transit riders.

There are better alternatives

As Edward Glaeser recently said in an interview with Vox.com:

There’s a strong consensus that maintaining existing infrastructure gives you much more bang for your buck. There have been diminishing returns to building new roads, particularly since we completed the National Highway System. Whereas if you have existing corridors with potholes, the returns to fixing that are very high. [See here for more.]

Another area of agreement among transportation economists is a profound enthusiasm for buses over trains. Bus rapid transit is considered a very high-return investment. These aren’t necessarily buses operating on crowded city streets; these are buses with dedicated lanes that can achieve almost the same speed as trains.

The beauty of buses, from a cost-benefit perspective, is you don’t need to lay down massive infrastructure that you’re stuck with forever. If a bus route doesn’t attract enough people, you switch the route. Or you stop running it. It’s flexible in a way that trains aren’t. And that’s tremendously valuable in a world of uncertainty.

Now, this is not about gutting the subway in New York or the Metro in Washington, DC. But for new stuff, investing in buses tends to make more sense given the modest densities of most American metropolitan areas.

No, I don’t hate light-rail

In fact I live in Seattle and take it to work daily. And I love trains in general. I once traveled from Hong Kong to Madrid completely by train (just thought I’d find a way to throw that in there). But I see critical problems with the current proposal and I have mixed feelings about Seattle’s current light-rail.

For one, Seattle’s light-rail is rarely full except during a morning rush hour and again during an evening one. And even during these peak times the capacity is fractions of that seen on Asian rail lines (I’ve lived in Seoul) and even many in Europe. Sure, some people may see that as a feature and not a bug, but when current capacity is easily met and we’re already talking about spending $54 billion on a new system I think it’s time to stop and think. Yes, the city is growing and will likely continue to grow, the question is what is the benefit of light-rail in that climate and are there better and cheaper alternatives.

This is not to mention my commute is actually 25 minutes longer under the current light-rail regime because the 71, 72, and 73 buses were all rerouted from an express lane route that led directly downtown. Now they go — guess where — to the nearest light-rail station.

Third, the four crucial light-rail stops downtown use the same tunnel as bus traffic and so are subject to the same delays. If a bus breaks down or is slow letting passengers off, the light-rail must wait for the bus to move on. If you are not from Seattle you might have though that the original $5 billion construction project would’ve gotten light-rail a dedicated track, but you’d only be correct outside of the downtown area. These are not theoretical delays; these are daily delays. This is not life’s biggest tragedy, but we all know the feeling of wanting to get home after a long day and when you’re on a motionless train stuck behind a bus (!) and are delayed for two minutes at each of four out of your total six stops you do start to question if the money was worth it.