I’m casually following along with a few of the lessons in Princeton’s Algorithms, Part 1 on Coursera. The course itself is taught in Java, but I thought completing some of the lessons in R would improve my R skills. The first activity I’ve completed is a percolation simulation using weighted quick-union with path compression. I’m not actually sure if this was one of the assignments, but it seemed cool so I thought I’d give it a try.

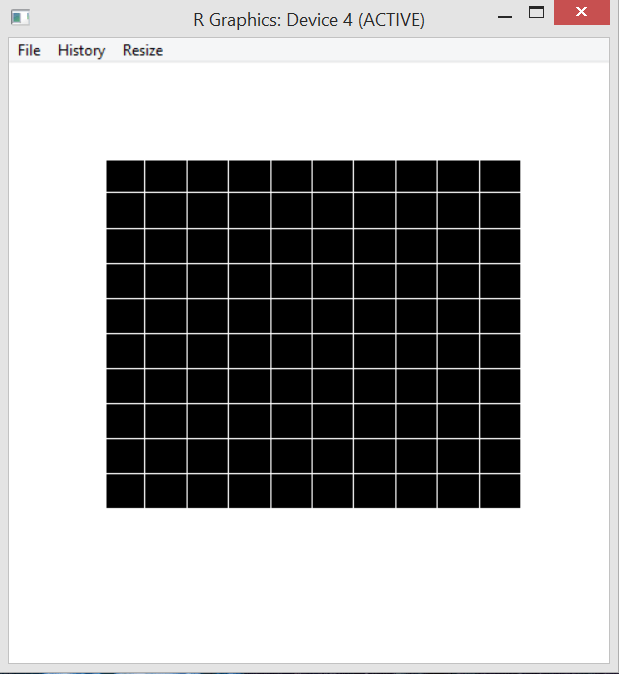

Percolation is meant to model physical or social systems where some type of blockage occurs. The algorithm taught in the class is to begin with full blockage and to randomly unblock one element until there is a path from one side of the system to another. The simplest method of doing this is to imagine a blocked grid. The initial blocked system is shown below.

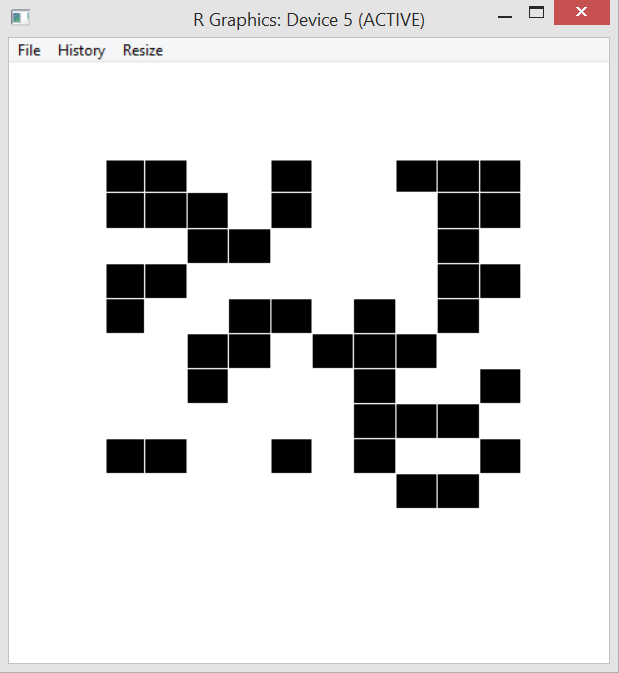

My algorithm removes one blockage per half second and this is modeled by turning the black box white. A totally percolated system is shown below. Notice there is now a path through the blockage – by starting at the bottom, following the open (white) squares up and to the left and then diagonally up and to the right.

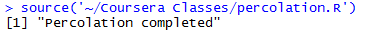

At the moment percolation is completed a message is printed to the console.

The code to initialize the board and percolated system and to run the clearing algorithm is shown below.

#################################################################### # James McCammon # 21 Feb 2015 # Percolation Algorithm Functions Version 1 #################################################################### # Load libraries library(shape) source("perc_functions.R") # Define variables nrows = 10 ncols = 10 nsites = nrows*ncols closedSites = 1:nsites numneighbors = 4 display = NULL #display = matrix(data=0, nrow=nrows, ncol=ncols) VTN = nsites + 1 VBN = nsites + 2 # Initailize board board = initBoard() initDisplay() initVTN() initVBN() # Run main main()

Created by Pretty R at inside-R.org

Most of the work is done in the set of functions below. This can definitely be improved, for example by incorporating an arbitrary list of neighbors into each site object rather than assuming the system is a square grid and determining neighbors by looking in the four quadrants around each site. I could also think harder about memory usage. Right now I just threw everything into the global environment and didn’t think too hard about memory usage or efficiency. Using the tracemem() function from the pryr shows there are a few times the board object is copied. I’ll probably play around with things and continue to improve them.

#################################################################### # James McCammon # 21 Feb 2015 # Percolation Algorithm Main Version 1 #################################################################### # Define main function main = function() { sleeptime = 0.5 while(!connected(VTN, VBN)) { randSite = getRandSite() board[[randSite]]$open = TRUE #location = trans2display(randSite) #write2display(location) filledrectangle(mid=c(display[[randSite]]$xmid, display[[randSite]]$ymid), display[[randSite]]$wx, display[[randSite]]$wy, col='white', lwd=1, lcol='white') neighbors = getNeighbors(randSite) for(i in 1:numneighbors) { if(is.null(neighbors[[i]])) next if(!isOpen(neighbors[[i]])) next join(randSite, neighbors[[i]]) } Sys.sleep(sleeptime) } print("Percolation completed") p = 1 - (length(closedSites)/nsites) return() } #Initalize the display initDisplay = function() { display <<- as.vector(1:nsites, mode='list') windows(5, 5) plot.new() xmid = 0 ymid = 1 wx = .1 wy = .1 index = 1 for(row in 1:nrows) { for(col in 1:ncols) { filledrectangle(mid=c(xmid, ymid), wx=wx, wy=wy, col='black', lwd=1, lcol='white') display[[index]] <<- list('xmid'=xmid, 'ymid'=ymid, 'wx'=wx, 'wy'=wy) index = index + 1 xmid = xmid + .1 } xmid = 0 ymid = ymid - .1 } } # Gets root getRoot = function(node) { while(node != board[[node]]$root) { board[[node]]$root <<- board[[board[[node]]$root]]$root node = board[[node]]$root } return(node) } # Checks if two notes are connected connected = function(node1, node2) { return(getRoot(node1) == getRoot(node2)) } # Initalize board initBoard = function() { board = as.vector(1:nsites, mode='list') board = lapply(board, function(i) list("index"=i, "size"=1, "root"=i, "open"=FALSE)) return(board) } # Initalize virtural top node initVTN = function() { board[[VTN]] <<- list("index"=VTN, "size"=(ncols + 1), "root"=VTN, "open"=FALSE) lastrow = nsites - ncols + 1 for(i in 1:ncols) { board[[i]]$root <<- board[[VTN]]$root } } # Initalize virtual bottom node initVBN = function() { board[[VBN]] <<- list("index"=VBN, "size"=(ncols + 1), "root"=VBN, "open"=FALSE) lastrow = nsites - ncols + 1 for(i in lastrow:nsites) { board[[i]]$root <<- board[[VBN]]$root } } # Choose random site getRandSite = function() { randSite = sample(closedSites, size=1) closedSites <<- closedSites[-which(closedSites==randSite)] return(randSite) } # Checks if site is open isOpen = function(site) { return(!(site%in%closedSites)) } # Get neighbors on a square board getNeighbors = function(index) { top = index - ncols if(top < 1) top = NULL bottom = index + ncols if(bottom > nsites) bottom = NULL left = index - 1 if(!(left%%ncols)) left = NULL right = index + 1 if(right%%ncols == 1) right = NULL return(list("tn"=top, "rn"=right, "bn"=bottom, "ln"=left)) } # Join two nodes join = function(node1, node2) { r1 = getRoot(node1) r2 = getRoot(node2) s1 = board[[r1]]$size s2 = board[[r2]]$size if(s1 > s2) { board[[r2]]$root <<- board[[r1]]$root board[[r1]]$size <<- s1 + s2 } else { board[[r1]]$root <<- board[[r2]]$root board[[r2]]$size <<- s2 + s1 } } #################################################################### # Functions for visualizing output with matrix #################################################################### # Translate location of site to matrix trans2display = function(index) { col = index%%ncols if(!col) col=ncols row = ceiling(index/nrows) return(list("row"=row, "col"=col)) } # Update the matrix display write2display = function(transObject) { display[transObject$row, transObject$col] <<- 1 }