My friend Ryan, who is also a math tutor at UW, and I are working our way through several math resources including Larry Wasserman’s famous All of Statistics. Here is a math problem:

Suppose we have  random variables

random variables  all distributed uniformly,

all distributed uniformly,  . We want to find the expected value of

. We want to find the expected value of ![\mathbb{E}[Y_n]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathbb%7BE%7D%5BY_n%5D+&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002) where

where  .

.

First, we need to find the Probability Density Function (PDF)  and we do so in the usual way, by first finding the Cumulative Distribution Function (CDF) and taking the derivative:

and we do so in the usual way, by first finding the Cumulative Distribution Function (CDF) and taking the derivative:

We want to be able to get this step:

But must show independence and we are not give that our  ‘s are in fact independent. Thanks to Ryan for helping me see that by definition:

‘s are in fact independent. Thanks to Ryan for helping me see that by definition:

However, note that in this case  is a unit

is a unit  with area

with area  equal to

equal to  . In other words

. In other words  . Our equation then simplifies:

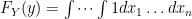

. Our equation then simplifies:

![F_Y(y) = \int dx_1 \dots \int dx_n = [F_X(y)]^n](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=F_Y%28y%29+%3D+%5Cint+dx_1+%5Cdots+%5Cint+dx_n+%3D+%5BF_X%28y%29%5D%5En+&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002) where

where  here is a generic random variable, by symmetry (all

here is a generic random variable, by symmetry (all  ‘s are identically distributed). This is the same answer we would’ve gotten if we made the iid assumption earlier and obtained

‘s are identically distributed). This is the same answer we would’ve gotten if we made the iid assumption earlier and obtained  . Originally, I had made this assumption by way of wishful thinking — and a bit of intuition, it does seem that

. Originally, I had made this assumption by way of wishful thinking — and a bit of intuition, it does seem that  uniformly distributed random variables would be independent — but Ryan corrected my mistake.

uniformly distributed random variables would be independent — but Ryan corrected my mistake.

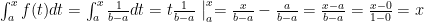

Now that we have  we can find

we can find  the PDF.

the PDF.

![f_Y(y) = \frac{d}{dy}F_Y(y) = \frac{d}{dy}[F_X(y)]^n](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=f_Y%28y%29+%3D+%5Cfrac%7Bd%7D%7Bdy%7DF_Y%28y%29+%3D+%5Cfrac%7Bd%7D%7Bdy%7D%5BF_X%28y%29%5D%5En+&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002)

![f_Y(y) = n[F_X(y)]^{n-1}f_X(y)](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=f_Y%28y%29+%3D+n%5BF_X%28y%29%5D%5E%7Bn-1%7Df_X%28y%29+&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002) by the chain rule.

by the chain rule.

Recall that the PDF  of a

of a  is

is  for

for ![x \in [0,1]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=x+%5Cin+%5B0%2C1%5D+&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002) . And by extension the CDF

. And by extension the CDF  for a

for a  is:

is:

.

.

Plugging these values into our equation above (and noting we have  not

not  meaning we simply replace the

meaning we simply replace the  we just derived with

we just derived with  as we would in any normal function) we have:

as we would in any normal function) we have:

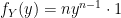

Finally, we are ready to take our expectation:

![\mathbb{E}[Y] = \int_{y\in A}yf_Y(y)dy = \int_0^1 yny^{n-1}dy = n\int_0^1 y^{n}dy = n\bigg[\frac{1}{n+1}y^{n+1}\bigg]_0^1 = \frac{n}{n+1}](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Cmathbb%7BE%7D%5BY%5D+%3D+%5Cint_%7By%5Cin+A%7Dyf_Y%28y%29dy+%3D+%5Cint_0%5E1+yny%5E%7Bn-1%7Ddy+%3D+n%5Cint_0%5E1+y%5E%7Bn%7Ddy+%3D+n%5Cbigg%5B%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7Bn%2B1%7Dy%5E%7Bn%2B1%7D%5Cbigg%5D_0%5E1+%3D+%5Cfrac%7Bn%7D%7Bn%2B1%7D&bg=ffffff&fg=000000&s=0&c=20201002)

Let’s take a moment and make sure this answer seems reasonable. First, note that if we have the trival case of  (which is simply

(which is simply  ;

;  in this case) we get

in this case) we get  . This makes sense! If

. This makes sense! If  then

then  is just a uniform random variable on the interval

is just a uniform random variable on the interval  to

to  . And the expected value of that random variable is

. And the expected value of that random variable is  which is exactly what we got.

which is exactly what we got.

Also notice that  . This also makes sense! If we take the maximum of 1 or 2 or 3

. This also makes sense! If we take the maximum of 1 or 2 or 3  ‘s each randomly drawn from the interval 0 to 1, we would expect the largest of them to be a bit above

‘s each randomly drawn from the interval 0 to 1, we would expect the largest of them to be a bit above  , the expected value for a single uniform random variable, but we wouldn’t expect to get values that are extremely close to 1 like .9. However, if we took the maximum of, say, 100

, the expected value for a single uniform random variable, but we wouldn’t expect to get values that are extremely close to 1 like .9. However, if we took the maximum of, say, 100  ‘s we would expect that at least one of them is going to be pretty close to 1 (and since we’re choosing the maximum that’s the one we would select). This doesn’t guarantee our math is correct (although it is), but it does give a gut check that what we derived is reasonable.

‘s we would expect that at least one of them is going to be pretty close to 1 (and since we’re choosing the maximum that’s the one we would select). This doesn’t guarantee our math is correct (although it is), but it does give a gut check that what we derived is reasonable.

We can further verify our answer by simulation in R, for example by choosing  (thanks to the fantastic Markup.su syntax highlighter):

(thanks to the fantastic Markup.su syntax highlighter):

################################################################

# R Simulation

################################################################

X = 5

Y = replicate(100000, max(runif(X)))

empirical = mean(Y)

theoretical = (X/(X+1)) #5/6 = 8.33 in this case

percent_diff = abs((empirical-theoretical)/empirical)*100

# print to console

empirical

theoretical

percent_diff

We can see from our results that our theoretical and empirical results differ by just 0.05% after 100,000 runs of our simulation.

> empirical

[1] 0.8337853

> theoretical

[1] 0.8333333

> percent_diff

[1] 0.0542087