Suppose we want to simulate  for

for  ,

,  . Suppose we want to do the same for the Cauchy distribution.

. Suppose we want to do the same for the Cauchy distribution.

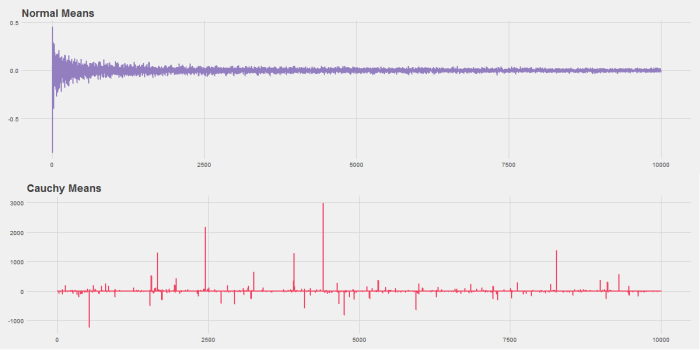

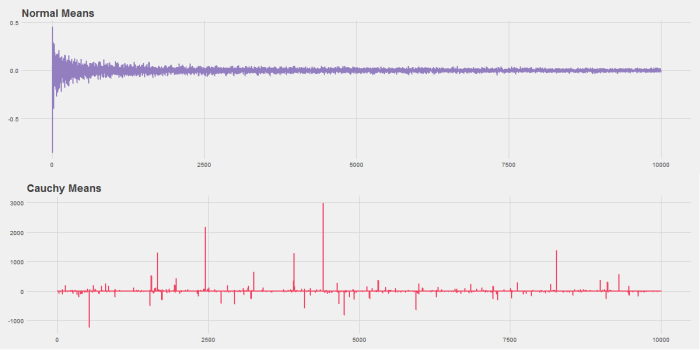

In other words, we want to draw several random variables from a normal distribution and then take the average. As  increases we should get closer to the mean of the distribution we’re drawing from, 0 in this case.

increases we should get closer to the mean of the distribution we’re drawing from, 0 in this case.

The R code below will do this. It produces this graph:

Notice that while the Normal distribution converges quickly the Cauchy never does. This is because the Cauchy distribution has fat tails and so extreme observations are common.

################################################################

# R Simulation

# James McCammon

# 2/20/2017

################################################################

# This script goes through the simulation of plotting both normal

# and Cauchy means for random vectors of size 1 to 10,000. It

# also demonstrates function creation and plotting.

# Highlight desired section and click "Run."

# Set working directory as needed

setwd("~/R Projects/All of Statistics")

###

# Calculate means and plot using base R

###

# Set seed for reproducibility

set.seed(271)

#

# Version 1: Simple

#

n = seq(from=1, to=10000, by=1)

y=sapply(n, FUN=function(x) sum(rnorm(x))/x)

plot(n, y, type="l")

#

# Version 2: Define a function

#

sim = function(x, FUN) {

sapply(x, FUN=function(x) sum(FUN(x))/x)

}

# Use function to plot normal means

x = seq(from=1, to=10000, by=1)

y1 = sim(x, rnorm)

plot(x, y1, type="l")

# Use function to plot Cauchy means

y2 = sim(x, rcauchy)

plot(x, y2, type="l")

#

# Version 3: More complex function

#

# This function has:

# (1) error checking

# (2) extra argument options

# (3) the ability to input any distribution R supports

sim = function(x, FUN, ...) {

if(!is.character(FUN)) stop('Please enter distribution as string.')

dists = c('rnorm',

'rbeta',

'rbinom',

'rcauchy',

'rchisq',

'rexp',

'rf',

'rgamma',

'rgeom',

'rhyper',

'rlnorm',

'rmultinom',

'rnbinom',

'rpois',

'rt',

'runif',

'rweibull')

if(is.na(match(FUN, dists))) stop(paste('Please enter a valid distribution from one of:', paste(dists, collapse=', ')))

FUN = get(FUN)

sapply(x, FUN=function(x) sum(FUN(x, ...))/x)

}

# We have to define our function in string form.

# This will throw error 1.

test1 = sim(x, rnorm)

# We have to input a distribution R supports.

# This will throw error 2.

test2 = sim(x, 'my_cool_function')

# We can input additional arguments like the

# mean, standard deviations, or other shape parameters.

test3 = sim(x, 'rnorm', mean=10, sd=2)

####

# Using ggplot2 to make pretty graph

###

# Load libraries

library(ggplot2)

library(ggthemes)

library(gridExtra)

png(filename='Ch3-Pr9.png', width=1200, height=600)

df1 = cbind.data.frame(x, y1)

p1 = ggplot(df1, aes(x=x, y=y1)) +

geom_line(size = 1, color='#937EBF') +

theme_fivethirtyeight() +

ggtitle("Normal Means")

df2 = cbind.data.frame(x, y2)

p2 = ggplot(df2, aes(x=x, y=y2)) +

geom_line(size = 1, color='#EF4664') +

theme_fivethirtyeight() +

ggtitle("Cauchy Means")

# Save charts

grid.arrange(p1,p2,nrow=2,ncol=1)

dev.off()

# Print charts to screen

grid.arrange(p1,p2,nrow=2,ncol=1)